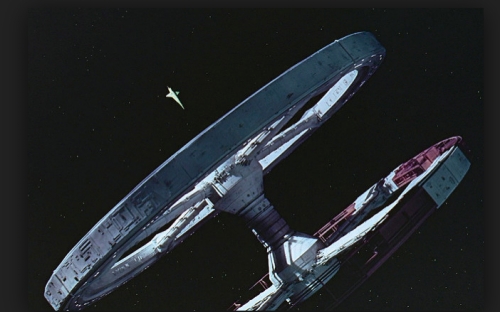

Aurora is Kim Stanley Robinson’s melancholic and ambitious tale about a generational seed ship on its final leg of a 160 year journey to an Earth analog planet which is actually a moon of a larger planet orbiting the star Tau Ceti, 11.9 light years from Earth. The name of the analog planet: Aurora. On board are ~2100 humans who are the seventh, and final, generation of an eventual settlement expedition that will land and live on Aurora. There are two main characters in the narrative; Ship, an artificial intelligence that is the ship itself; and Freya, a woman around which Ship builds the narrative of the book told through its “eyes” (cameras). Ship itself is comprised of two rotating rings, each comprised of twelve segments (or biomes), with each ring holding about 1000 humans. The biomes represent biologically and ecologically independent environments.

Aurora is also divided up into three thematic sections: The Arrival, On Aurora, The Return. These sections are my interpretation, not reflective of the actual named parts of Aurora.

Part I – The Arrival:

As Ship approaches Aurora, a moon of the planet Tau Ceti e, which orbits Tau Ceti, we find that the infrastructure of Ship is in a state of disarray. Systems are failing and in need of constant repair, biome biology has become increasingly sensitive, and the IQs of this final generation of humans is the lowest it’s been. The populace is generally unhappy and dissatisfied with conditions on the ship. They are more than ready to depart. Devi, Freya’s mother, is suffering from cancer and soon succumbs just as they reach Aurora.

Part II – On Aurora:

Most, but not all, passengers are eager to leave the decaying Ship and begin establishing an outpost on Aurora. The work will be hard while in inhospitable conditions. Approximately half of them move to the cold, windy, and lifeless surface, using molecular printers to create all the tools and resources they need. Even though they never leave their protection of suits, accidents happen and they soon learn that Aurora is even more inhospitable than believed. People are suddenly and quickly dying from an unknown prion that seems to be found in the sand of the planet. It quickly becomes apparent that the mission is doomed to failure . . . 160 years for naught. Two options are proposed: move to the next candidate planet, or return to Earth. There seems no other option since all but one person who landed on Aurora died.

Part III – The Return:

Put to a vote half of those remaining on the ship choose to move on to the next planet, the rest vote to return to Earth, knowing they will be doing so on a Ship that is quickly succumbing to the forces of entropy. Ship is divided into its two rings, one given to each group, and the story follows the return group to Earth. Plans for another generational return via procreation soon evaporates. Starvation, suicide, infertility, Ship failure and the like take their toll. Ship receives communication from Earth that they’ve developed a method of suspended animation that should get them the rest of the way home.

It’s clear the Robinson did his homework while writing Aurora. It oozes speculated science on how humanity could journey to another star via a generational ship. Is the science accurate? In most respects, probably not. I expect building a self contained environment and flinging it to a fraction of the speed of light via laser while keeping seven generations of humans alive for 160 years in the cold of space is something current scientists have no tangible idea how to do, other than via speculation. But the extrapolation of said science to arrive at the overall premise of Aurora is sound . . . or at least comes across as sound for the sake of fiction.

And that’s one of Aurora‘s problems, at least for this reader. The story is steeped in too much science, often told from the point of view of an analytic artificial intelligence. Yes, at times Aurora is beautiful, powerful, and melancholy . . . its middle sections are also as dry as the Sahara and are a real struggle to wade through. Thankfully the book isn’t overly long, it only feels like it, especially during the middle sections.

Ship is populated with many characters, most of them mentioned in passing, few of them ever given memorable attention. As previously mentioned the two main characters are Freya and Ship. Freya is the daughter of Ship’s main engineer (Devi) on the last leg of the journey to the planet Aurora. Being so, Freya inherits many of the problems plaguing Ship. While her characterization is strong, it’s not overly interesting nor is she really likable. The other character, of course, is Ship, who is significantly more interesting than, and equally as complex as, Freya. When a reader is more interested in a quantum computer and sad that an artificial intelligence “dies,” rather than being happy a significant number of humans return to Earth alive . . . you might have characterization and relatability issues.

Finally, the title of the book is Aurora. It’s an enigma since very little time is spent on the planet. It comes across as a destination device simply for something catastrophic to go wrong, with little effort on Robinson’s part to develop it as anything more than a quick stop over point. The book is essentially about Ship, the people aboard it, and every detailed sacrifice and challenge they face. Aurora is not about its namesake planet or anything that happens there other than being infected with prions which brings a tragic end to the hope of settlement. If the name of Ship was Aurora, an interesting character . . . then you’d have an appropriate title.

Bottomline:

There’s little doubt that Kim Stanley Robinson crafted Aurora to be a cautionary tale about the tremendous risks involved with space travel and the settling of alien planets. The takeaway seems to be that humans are far too fragile for such work and that it’s best left to machines and artificial intelligence. Aurora is not a tale of the triumph of discovery, but of the despair of loss and the triumph of survival. Along with it comes a profound sense of beautiful melancholy that can often make it a difficult read.

★★★★☆ (4 out of 5 stars) - I really liked it.